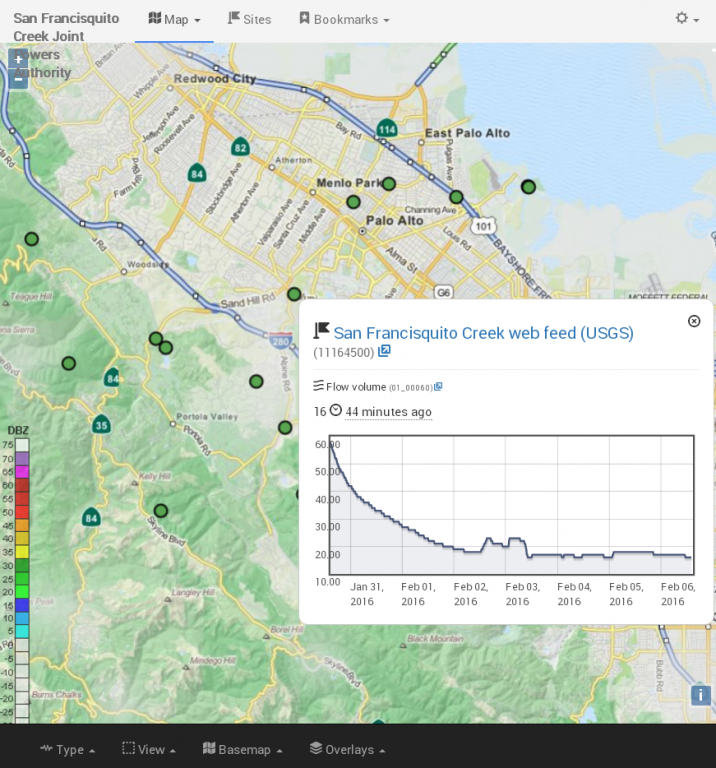

In the news February 2016: “Predicting El Niño’s flood risk: How new warning systems save lives, property”. OneRain’s Contrail® software provides the real-time monitoring and alerting for San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority’s newly launched Flood Early Warning System. Check out this great article by journalist, Lisa Krieger with the Mercury News, focused on how automated remote data systems are helping protect communities in the San Francisco Bay area.

News Source: Lisa Krieger, San Jose Mercury News

Four winters ago, as worried rescuers watched the quickly rising waters of a Peninsula creek and tried to decide whether to alert local residents, they turned to a small green plant for guidance.

“You see that shrub?” one public safety official said. “When it’s under water, we’re going to start evacuating.”

Today, that sentinel shrub has been replaced by a sophisticated network of gauges, sensors and computers that can save lives and property — not only in flood-prone Menlo Park, Palo Alto and East Palo Alto, but also in vulnerable South Bay and East Bay communities.

Counting El Niño’s raindrops in distant mountains, the new flood-prediction systems are for the first time allowing the Bay Area to anticipate disasters, not merely respond to them.

“We can ramp up, adding resources and personnel,” said Menlo Park Fire Chief Harold Schapelhouman. “It becomes part of normal planning.”

A revolution in technology allows for the highly automated and near-instantaneous analysis of enormous volumes of digital information about water flow.

It works like this: Separate streams of data — collected from mountain peaks and rushing creeks — are integrated into huge databases. Computers then track rising waters and predict flood risk, based on creekbed capacity and the surrounding landscape.

As waters run high, the computers can issue an electronic flood alert to local residents downstream. For instance, mid-Peninsula residents who are registered to get an alert — by text or email — are kept informed about four different flood-prone locations along San Francisquito Creek. They will be notified nearly two hours in advance of the water overflowing its banks.

“We know what is coming down the system,” said Len Materman of San Francisquito Creek’s Joint Powers Authority, which has a newly expanded system of automated rain and creek gauges perched 2,000 feet above the vulnerable mid-Peninsula cities. “We can give people solid information for decision-making” about such things as when to sandbag, get electronics and antiques off the floor or seek higher ground.

To be sure, even the most high-tech upstream tools can’t predict flooding from surprise local sources, such as a suddenly downed tree or a blocked storm drain.

While we’ve long been able to accurately forecast flooding on major water routes like the Sacramento River, the risk along smaller urban tributaries — prone to flash floods, especially if lined with concrete — has been far tougher to predict.

Flooding is the leading cause of severe weather-related deaths in the U.S., causing 75 to 200 drownings per year. Because cars can be swept away in only 1 to 2 feet of water, about half of the drownings are vehicle-related.

In the last strong El Niño in the winter of 1997-1998, 1,700 homes were flooded on the Peninsula, and some residents had to be evacuated by boat. There also was damage in other Bay Area communities.

But history isn’t much help in predicting future risk because every storm is unique, with different rainfall patterns, experts say.

Steve Fitzgerald, president of the National Hydrologic Warning Council, has witnessed the recent and dramatic expansion of real-time, high-quality hydrologic information.

In 1983, as Hurricane Alicia bore down on his city of Houston, he was frustrated and fatigued by attempts to identify danger. Working 24 hours straight, he used a Wang computer to plot the data delivered by the county’s 12 rain gauges, imperfect devices rigged with weights and cables. Each graph took him 45 minutes to complete. Then, as rains pounded the city, the information quickly became obsolete and needed to be updated.

Now computer analyses of his county’s 150 electronic gauges and sensors take only seconds. “There has been quite a transformation,” said Fitzgerald, chief engineer of the Harris County Flood Control District.

Other cities with state-of-the-art flood prediction capabilities include Denver, Las Vegas, Los Angeles and Charlotte, North Carolina.

In the Bay Area, the newly expanded mid-Peninsula network was designed by hydrologists and data-crunchers at Berkeley-based Balance Hydrologics, using property volunteered by Stanford University, the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District and San Mateo County Parks.

The Santa Clara Valley Water District has a network of 70 stream and rain gauges throughout the county, located along Los Gatos Creek, Stevens Creek, Alamitos Creek, Uvas Creek, the Guadalupe River and other sites.

Contra Costa County has three stream gauges, 29 rain gauges and one reservoir gauge, and it just received a grant to add 10 more stream gauges. It monitors Marsh Creek in the eastern part of the county and Walnut Creek in the central part of the county.

In Alameda County, a network of about 90 rain and stream gauges collects data used to estimate potential flood conditions. In the future, the county plans to expand its network to develop a database and Web tool that can be downloaded by residents.

The magic of the new technologies is that they can identify an emerging risk miles — and hours — away. Gauges, powered by solar panels, can accurately send electronic signals to data loggers via radio, landlines, cellphones or satellites. This data is more quickly analyzed due to increased computer power. And the flood risk is instantly communicated to nearby residents.

But, Materman said, it’s not enough to just gather information: “The first half of the problem is better data. The second half is: How do the public and emergency responders use that data?”

Increasingly, residents can go online to track water levels and changes in flow rates, said Gary Kremen, a board member of the Santa Clara Valley Water District. “There is greater transparency. It is empowering.”

But how well will this all work?

This winter’s El Niño could put it to the test.

“It is a work in progress,” Materman said. “Our work is based on models. We’ll need to ‘ground truth’ it.”

It’s far better, though, than keeping a watchful eye on a shrub, he said. “But it will take a real storm to see whether it behaves like we predict it should.”

- BETTER GAUGING STATIONS: Rain gauges are 10-foot-tall pipes with a funnel, bucket and tipping mechanism at the top; each tip measures 0.04 inches of rainfall. Creek gauges have a membrane that precisely measures the depth of water and converts it into a flow rate, expressed in cubic feet per second.

- IMPROVED DATA TRANSMISSION: Each time the rain gauge’s lever tips, its tiny internal computer sends a high-frequency radio transmission with the tip counter numbers to a receiver or repeater, then to a computer system. In creeks, the gauges convert the water’s depth to a flow rate, then transmit signals via phone lines.

- FASTER ANALYSIS: With ever-increasing computer power, software processes the many signals into a computer database, which monitors the information as it is received. It triggers a warning when certain thresholds — say, water filling 80 percent of a creek’s capacity — are reached. Because different locations have different flood risks, the warnings can be localized.

- ADVANCED COMPUTER MODELING: Instant access to project data is available through a cloud-based data center and can be viewed in real time or as a graph to identify trends. Using advanced math, topographic models can predict where and when water will likely go, if flooding occurs.

- CELLPHONE ALERT SYSTEMS. In 2012, a California law went into effect that allows emergency alerts to be sent to cellphones, allowing flood control agencies to send automated warnings directly to the cell towers of major U.S. carriers, which then transmit those messages by text or email to phones. Residents of some communities can also track flood risk on websites.

###

Full Article Source: http://www.mercurynews.com/drought/ci_29453899/predicting-el-ninos-flood-risk-how-new-warning

Contact Journalist Lisa M. Krieger at 650-492-4098. Follow her at Twitter.com/LisaMKrieger and Facebook.com/LisaMKrieger.